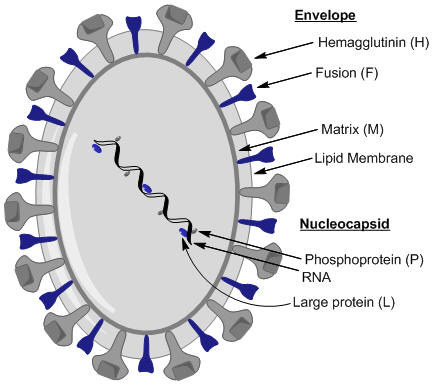

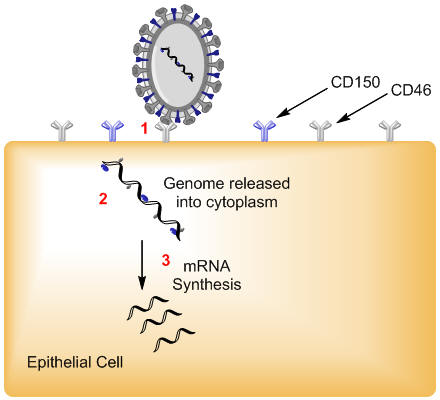

Measles VirusOverview: Measles virus, also known as rubeola virus, is the causative agent of measles. The virus is a member of the genus Morbillivirus in the family Paramyxoviridae. It is roughly 100 nm to 200 nm in diameter and contains an inner nucleocapsid core that is 18 nm in diameter with a negative-sense, single-stranded, non-segmented RNA genome. Out of the six structural proteins its genome encodes, only two envelope membrane proteins are important in pathogenesis and disease progression, namely, the fusion protein (F protein), which is responsible for the fusion of the virus into the host cell membrane, viral penetration, and hemolysis, and the hemagglutinin protein (H protein), which is responsible for adsorption of virus to cells. A third envelope protein known as the matrix protein (M protein) lines the inner surface and is 34 kDa (kiloDaltons) in size; the three remaining structural proteins are complexed to the virus' genome, which comprises approximately 16000 nucleotides (Figure 1). Figure 1. Schematic of the measles virus. Note: nucleoprotein (N) which surround the RNA in a tube-like manner (nucleocapsid) has not been illustrated in this rendition. Transmission: Humans are the only species susceptible to the measles virus. It is typically spread by airborne particles such as respiratory droplets coming from nasal or oral cavities of an infected individual. Pathogenicity: Once the virus has gained entry into its host, it anchors itself to host endothelial and respiratory epithelial cells via the complement regulatory cofactor protein CD46 (Figure 2). The H protein of the virus interacts with the F protein to mediate attachment and fusion of the viral envelope with the host cellular receptors upon attachment. CD46 is a complement regulatory molecule expressed on virtually all nucleated cells in humans. Another identified receptor is CD150; together, both receptors are referred to as signalling lymphocyte activation molecule (SLAM). SLAM is expressed on activated T and B lymphocytes and antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells. The binding sites on viral H protein for these receptors overlap and strains of measles virus differ in the efficiency with which each receptor is used. For instance, wild-type measles virus binds to cells primarily through the cellular receptor SLAM, whereas most vaccine strains bind to CD46, as well as to SLAM. Thus, by targeting cells associated with humoral immune responses and cell-mediated immunity, measles virus is able to establish itself in the host and evade the non-specific defense systems such as complement-mediated killing for a short, but effective period of time. Figure 2. Entry of measles virus into target respiratory epithelial cell. Clinical Infections: The acute infection associated with the virus is highly contagious, infecting 90% of individuals lacking immunity via vaccination. In fact, prior to 1963, getting measles was an expected life event. Each year in the U.S. there were approximately three to four million cases and an average of 450 deaths, with epidemic cycles every two to three years. More than half the population had measles by the time they were six years old, and 90 % had the disease by the time they were 15. Moreover, measles infections having a relatively short incubation period, typically between 7 and 18 days. The infection is characterized by rashes, cough, fever, ear infections, pneumonia, conjunctivitis, diarrhea, seizures, brain damage, and sometimes death (although rare). Symptoms: Initial symptoms of the infection include coughing, runny nose, and mildly inflamed conjunctiva(conjunctiva is the clear mucous membrane consisting of cells and underlying basement membrane that covers the white part of the eye and lines the inside of the eyelids). These symptoms are then followed by a rash that starts three days after these initial symptoms. Koplik spots, which are small, red, irregularly-shaped spots with blue-white centers also occur on the mucosal surface of the oral cavity (Figure 3). The maculopapular rash appears first on the head, and then progressively spreads downward on the victim’s body. Figure 3. This was a patient who presented with Koplik’s spots on palate due to pre-eruptive measles on day 3 of the illness. Vaccination: The mortality rate is only

two individuals in

every 1000 infected patients in developed

countries, but this number increases to 150 deaths for every 1000

infected patients in developing countries. The

only way to prevent measles

infection is through vaccination.

The Schwarz vaccine is typically used and is

recommended that this live-attenuated

virus be administered to every child fifteen months

of age. The vaccine

results in over 95% seroconversion (the

development of detectable specific antibodies to

microorganisms in the blood serum as a result of

infection or immunization) in patients,

providing them the ability to

fight off infections from this virus, and a

booster shot is recommended to

ensure lifelong immunity.

Vaccination, however, is difficult to ensure for

every child in countries that are poor,

especially when this

virus is the leading cause of

vaccine-preventable childhood mortality. Due to

this, a vaccination campaign

was started by several partners (including the

American Red Cross and World

Health Organization) in order to increase

awareness regarding the simple

avoidance of this disease. Globally, measles-related deaths decreased 60% References: De Quadros, C., Olive, J., Hersh, B., Strassburg, M., Henderson, D., Brandling-Bennett, D., & Alleyne, G. (1996). Measlies elimination in the Americas. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 275: 224-229.

Ferreira, C.S.A., Frenzke, M., Leonard, V.H.J.,

Welstead, G.G., Richardson, C.D., Cattaneo, R.

(2010). Measles Virus Infection of Alveolar

Macrophages and Dendritic Cells Precedes Spread Sension, M.G., Quinn T.C., Markowitz, L.E., Linnan, M.J., Jones, T.S., Francis, H.L., Nzilambi, N., Duma, M.N., Ryder, R.W. (1988). Measles in hospitalized African children with human immunodeficiency virus. American Journal of Diseases of Children, 142: 1271–1272. |