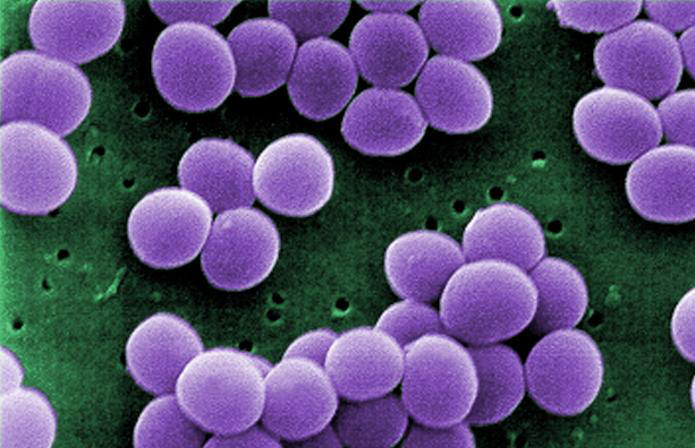

Staphylococcus aureusOverview: Staphylococcus aureus is a Gram-positive, coccus-shaped facultative anaerobe and a member of the Staphylococcaceae family and Bacillales order (Figure 1). S. aureus is frequently part of the skin flora found in the nose and on skin. It can, however, cause a wide range of illnesses from minor skin infections, such as pimples, impetigo, and scalded skin syndrome, to life-threatening diseases such as pneumonia, meningitis, osteomyelitis, endocarditis, and toxic shock syndrome. Infections of the blood can carry the bacteria to various deep tissues, including bones, joints, organs, and the respiratory system. Furthermore, S. aureus is catalase-positive and mannitol-positive. A coagulase test determines pathogenic from non-pathogenic staphylocci, in which S. aureus would test positive. Figure 1. This scanning electron micrograph shows Staphylococcus aureus bacteria. Colonial Morphology and Identification: Colonial morphology of S. aureus in culture is typically raised, growing smooth medium to large colonies that are slightly translucent with creamy-yellow pigmentation. Most strains are beta-hemolytic, suggesting that they are able to lyse red blood cells and grow on blood agar medium. Virulence and Pathogenicity: Polymers of glycerol or ribitol phosphate (teichoic acids) are attached to peptidoglycan molecules on the cell wall of S. aureus, making it antigenic. Recall that teichoic acid can be used by bacteria to attach to mucosal membranes, and its release during bacterial cell lysis into the bloodstream may cause fever, decrease in blood pressure due to blood vessel dilation, and possibly toxic shock (Figure 2). Furthermore, some strains of S. aureus vary from others in morphology by the presence of a capsule composed of protein A (SpA), which can impede host polymononuclear phagocytosis by binding to immunoglobulin G (IgG) Fc (constant region). SpA is also a potent activator of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) receptor 1 (TNFR1) signaling, inducing both chemokine expression and TNF-converting enzyme-dependent soluble TNFR1 shedding, which has anti-inflammatory consequences, particularly in the lung. Moreover, aggregation of S. aureus bacteria is attributed to the presence of coagulase and fibrogenin on their cell wall surface, which bind together to produce the clusters observed microscopically (Figure 1). Figure 2. This patient presented with a 'strawberry tongue', and was diagnosed with Toxic Shock Syndrome caused by Staphylococcus aureus. In fact, 'Menstrual' Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS) emerged as a public health threat to women of reproductive age in 1979 to 1980. Depending on the particular strain, there are several kinds of toxins attributed to S. aureus virulence. Exotoxins can include toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1), exfoliatins, and enterotoxins. Others may include alpha-toxin, beta-toxin, delta-toxin, and bicomponent toxins such as Panton-Valentine leukocidin. Factors including protein A, Staphyloxanthin pigment, clumping factor, coagulase, hyaluronidase, leukocidin, and biofilm production can also affect the virulence (Forbes et al., 2007). Exotoxin TSST-1 causes toxic shock syndrome by stimulating the release of large amounts of interleukin-1 (IL-1) by human monocytes, interleukin-2 (IL-2), and tumour necrosis factor. Similarly, it induces the expression of IL-2 receptors and the proliferation of human T lymphocytes. It does this by binding to MHC class II molecules and the exotonin is produced by most strains of S. aureus (Scholl et al., 1989). In general, the toxin is not produced by bacteria growing in the blood; rather, it is produced at the local site of an infection, and then enters the bloodstream. Exfoliative toxins are the sole agents responsible for staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS), a disease predominantly affecting infants and characterized by the loss of superficial skin layers, dehydration, and secondary infections. Exfoliatins are serine proteases with high substrate specificity, which selectively recognize and cleave (hydrolyse) desmosomal cadherins only in the superficial layers of the skin, which is directly responsible for the clinical manifestation of SSSS (Bukowski et al., 2010). Alpha-toxin secreted by this pathogen binds to cell surface receptors and form the heptameric pores. This pore allows the exchange of monovalent ions, resulting in DNA fragmentation and eventually apoptosis. Higher concentrations result in the toxin absorbing nonspecifically to the lipid bilayer and forming large, Ca2+ permissive pores. This, in turn, results in massive necrosis and other secondary cellular reactions triggered by the uncontrolled Ca2+ influx. Similarly, the cytotoxin Panton-Valentine leukocidin forms β-pores in target cells, causing necrotic lesions involving the skin or mucosa, including necrotic hemorrhagic pneumonia. More specifically, this cytokin assembles in the membrane of host defense cells, particularly white blood cells, monocytes and macrophages. The two subunits fit together and form a ring with a central pore through which cell contents leak and which acts as a superantigen. Epidemiology: As mentioned earluer, S. aureus can be found in the normal flora of humans. Anterior nares, the nasopharynx, the perineal area, and the skin commonly house small colonies of S. aureus (Forbes et al., 2007). This organism can be carried by a symptomless host and transmitted via direct contact with a carrier or indirectly by touching a contaminated item. Lipoteichoic adherence complexes are used to hold to and colonize within the housing tissues. In addition, spread of the bacteria from its normal site of habitation to an abnormal site can result from a tear in the tissue from a wound or surgery. This species is often associated with immunocompromised patients, since many outbreaks occur in healthcare facilities due to contact between patients and asymptomatic healthcare professionals. References: Bukowski, M., Wladyka, B., & Dubin, G. (2010). Exfoliative Toxins of Staphylococcus aureus. Toxins, 2(5): 1148-1165. Forbes, B.A., Sham, D.F. & Weissfeld, A. S. (2007). Bailey & Scott's diagnostic microbiology (12th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby. Scholl, P., Diez, A. et al. (1989). Toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 binds to major histocompatibility complex class II molecules. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 86: 4210-4214. |