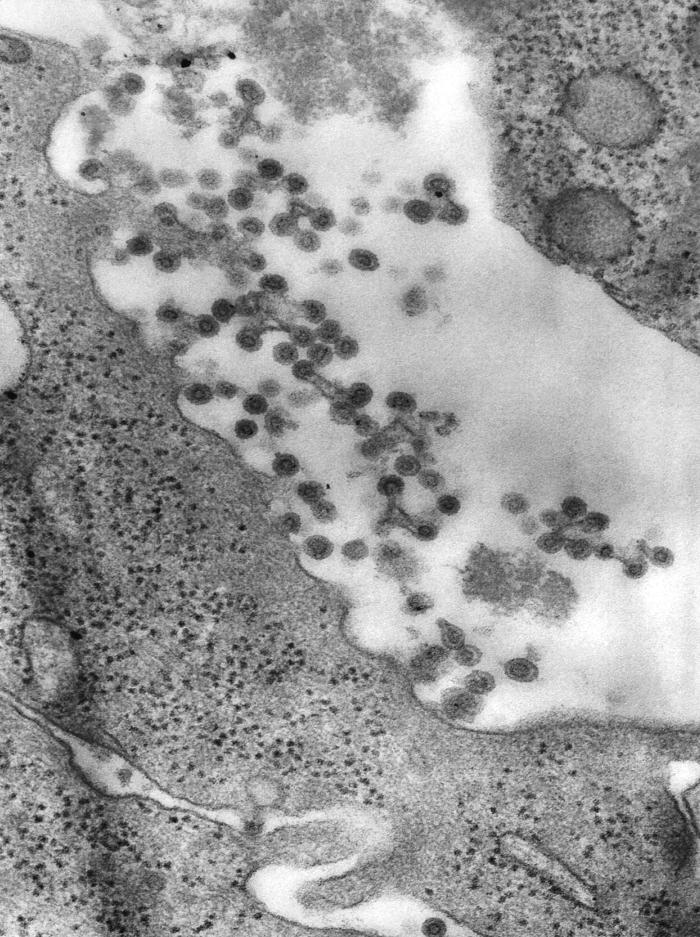

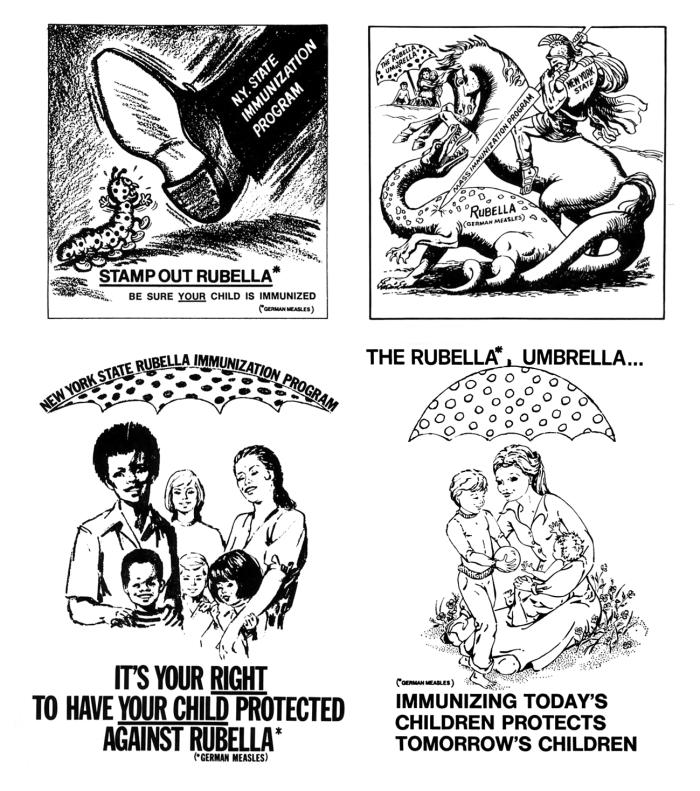

Rubella VirusOverview: Rubella (often referred to as German measles or 3-day measles) is a respiratory viral infection caused by the rubella virus (Figure 1). Rubella virus is an enveloped, single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus and a member of the Togaviridae family and the sole member of the genus Rubivirus; only one serotype has been identified. The virus is spherical and ranges from 40 nm (nanometres) to 80 nm in diameter. Its electron-dense core (nucleocapsid) is roughly 30 to 35 nm in size and is made up of polypeptide C, while glycosylated lipoproteins (hemagglutinin) make-up the outer envelope of the organism. The key virulence factors of this pathogen are virus-specific polypeptides E1 and E2 that project 5 to 6 nm above the surface of the outer envelope. Figure 1. This negatively-stained transmission electron micrograph demonstrates the presence of rubella virus virions, as they were in the process of budding from the host cell surface to be freed into the host’s system, thereby, producing an enveloped virus particle, which means that after budding, the spherical virions' icosahedral capsid is enclosed in the host cell membrane. Clinical Infections: Rubella is classified into two categories, namely, postnatal and congenital. In postnatal rubella, the virus enters the body through nasopharynx and attaches to respiratory epithelium before spreading throughout the lymphatics. Congenital rubella occurs when a pregnant woman is infected with the virus and passes it on to the fetus via the bloodstream (Edlich et al., 2005). The infection occurs transplacentally at the time the virus is present in the mother. Cells from the early fetal period that are infected with the virus have been shown to have lower mitotic activity, which likely results in chromosomal breakage, thus limiting cellular proliferation and protein production. When a mother becomes infected with rubella virus, the baby is at high risk of being born with congenital organ defects, such as cataracts, heart disease, mental retardation, deafness, and liver and spleen damage. There is at least a 20% chance of damage to the fetus if a woman is infected early in pregnancy. The rubella virus is responsible for causing cytopathic effects, including breaks and nicks in the host cell’s chromosomes. Aside from congenital rubella, the infection caused by this pathogen is rather harmless. Common symptoms include a mild fever (99°F to 100°F) and a rash that lasts two to three days, which develops approximately 14 to 23 days after exposure (the incubation period). The rash that develops is in the form of small pink or red dots which start on the face and spreads downwards (Figure 2). The size of these dots are approximately 1 to 4 mm in diameter. Other symptoms may include swollen lymph nodes in the neck and behind the ears. Complications occur more frequently in adult women, who may experience arthritis or arthralgia, often affecting the fingers, wrists and knees. However, these joint symptoms rarely last for more than a month after appearance of the rash. Figure 2. The young boy pictured here, displayed the characteristic maculopapular rash indicative of rubella. Diagnosis: The diagnostic tools used among medical professionals to detect whether a person is infected with the virus include virus culture laboratory testing and blood tests using the indirect Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) method to see whether the blood sample contains rubella antibodies. If rubella-specific antibodies are found, it indicates that the person has been exposed to the pathogen and at one point generated an immune response against the virus. Furthermore, there are no treatments available that will help one fight off a rubella infection; the virus must simply run its course. However, if a pregnant woman is infected with the rubella virus, the doctor may prescribe a hyperimmune globulin that quickly opsonizes the virus to prevent it from infecting vulnerable fetal cells; in turn, this lowers the risks of birth defects in the unborn child. Vaccination: In the early 1960s, more than 20,000 babies were born with congenital rubella syndrome during an outbreak of rubella. This epidemic cost the country an estimated $1.5 billion. After the live attenuated (weakened) rubella vaccine was first licensed in 1969, the frequency of rubella cases decreased significantly in North America (Figure 3). There are many other locations worldwide where rubella infections are still common, such as Mexico and parts of Europe. These locations may not have access to rubella immunizations or have just recently begun routine rubella immunizations. Although it is available as a single preparation, it is recommended that in most cases rubella vaccine be given as part of the MMR vaccine (protecting against measles, mumps, and rubella). This vaccine is recommended to infants at 12 to 15 months (not earlier) and a second dose at 4 to 6 years old (before kindergarten or 1st grade). It has been found that 95% of those who get vaccinated at the age of 12 months or older develop life long immunity with only a single vaccination. This shows how affective the MMR vaccine is and how it is crucial that all infants get this vaccine, especially girls (to prevent rubella during future pregnancies). Figure 3. Shown here is a grouping of four illustrations that were used in public service campaigns to encourage parents to vaccinate their children against Rubella in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Click to enlarge. References: Edlich, R.F., Winters, K.L., Long, W.B., & Gubler, K.D. (2005). Rubella and congenital rubella (German measles). Journal of Long-Term Effects of Medical Implants, 15(3): 319–328. |